I'm not sure amazon permits to sell books for free I'll find a solution anyway.

A couple of things to know before start coding...

This chapter is completely different from the rest of the book. It's dedicated to the developers. PostgreSQL is a fantastic infrastructure for building powerful and scalable applications. In order to use al its potential there are some things to consider. In particular if coming from other DBMS there are subtle caveats that can make the difference between a magnificent success or a miserable failure.SQL is your friend

Recently the rise of the NOSQL approach,has shown more than ever how SQL is a fundamental requirement for managing the data efficiently. All the shortcuts, like the ORMs or the SQL engines implemented over the NOSQL systems, sooner or later will show their limits. Despite the bad reputation around it, the SQL language is very simple to understand. Purposely built with few simple English words is a powerful tool set for accessing, managing or defining the data model. Unfortunately this simplicity have a cost. The language must be parsed and converted into the database structure and sometimes there is a misunderstanding between what the developer wants and what the database understands.Mastering the SQL is a slow and difficult process and requires some sort of empathy with the DBMS. Asking for advice to the database administrator is a good idea to get introduced in the the database mind. Having a few words with the DBA is a good idea in any case though.

Design comes first

One of the worst mistakes when building an application is to forget about the foundation, the database. With the rise of the ORM this is happening more frequently than it could be expected. Sometimes the database itself is considered as storage, one of the biggest mistake possible.Forgetting about the database design is like building a skyscraper from the top. If unfortunately the project is successful there are good chances to see it crumbling down instead of making money.

In particular one of the PostgreSQL's features, the MVCC, is completely ignored at design time. In 7.6 it's explained how is implemented and what are the risks when designing a data model. It doesn't matter if the database is simple or the project is small. Nobody knows how successful could be a new idea. Having a robust design will make the project to scale properly.

Clean coding

One of the the first things a developer learns is how to write formatted code. The purpose of having clean code is double. It simplifies the code's reading to the other developers and improves the code management when, for example, is changed months after the writing. In this good practice the SQL seems to be an exception. Is quite common to find long queries written all lowercase, on one single line with keywords used as identifier. Trying just to understand what such query does is a nightmare. What follow is a list of good practice for writing decent SQL and avoid a massive headache to your DBA. If you don't have a DBA see 11.4.The identifier's name

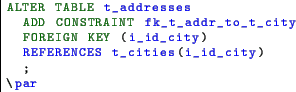

Any DBMS have its way of managing the identifiers. PostgreSQL transforms the identifier's name in lowercase. This doesn't work very well with the camel case, however it's still possible to mix upper and lower case letters enclosing the identifier name between double quotes. This makes the code difficult to read and to maintain. Using the underscores in the old fashion way it makes things simpler.Self explaining schema

When a database structure becomes complex is very difficult to say what is what and how it relates with the other objects. A design diagram or a data dictionary can help. But they can be outdated or maybe are not generally accessible. Adopting a simple prefix to add to the relation's name will give an immediate outlook of the object's kind.| Object | Prefix |

|---|---|

| Table | t_ |

| View | v_ |

| Btree Index | idx_bt_ |

| GiST Index | idx_gst_ |

| GIN Index | idx_gin_ |

| Unique index | u_idx_ |

| Primary key | pk_ |

| Foreign key | fk_ |

| Check | chk_ |

| Unique key | uk_ |

| Type | ty_ |

| Sql function | fn_sql_ |

| PlPgsql function | fn_plpg_ |

| PlPython function | fn_plpy_ |

| PlPerl function | fn_plpr_ |

| Trigger | trg_ |

| rule | rul_ |

A similar approach can be used for the column names, making the data type immediately recognisable.

| Type | Prefix |

|---|---|

| Character | c_ |

| Character varying | v_ |

| Integer | i_ |

| Text | t_ |

| Bytea | by_ |

| Numeric | n_ |

| Timestamp | ts_ |

| Date | d_ |

| Double precision | dp_ |

| Hstore | hs_ |

| Custom data type | ty_ |

Query formatting

Having a properly formatted query helps to understand which objects are involved in the data retrieval and the relations between them. Even with a very simple query a careless writing can make it very difficult to understand.A query like this have many issues .

- using lowercase keywords it makes difficult to spot them

- the wildcard * hides which columns are effectively needed; it retrieves all the columns consuming more bandwidth than required; it prevents the index only scans

- the meaningless aliases like a and b it make difficult to understand which relations are involved.

- writing a statement with no indenting it makes difficult to understand the query's logic.

- All SQL keywords should be in upper case

- All the identifiers and kewrords should be grouped by line break and indented at the same level

- In the SELECT list specify all and only the columns required by the query

- Avoid the auto join in order to make clear the relation's logic

- Adopt meaningful aliases